This story is part of the

Lang's European Fairy Tales I unit. Story source:

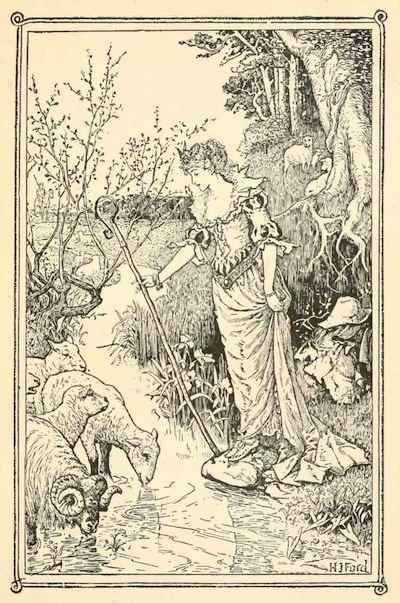

The Brown Fairy Book by Andrew Lang, illustrated by H. J. Ford (1904).

Kisa the Cat

(an Icelandic tale)

Once upon a time, there lived a queen who had a beautiful cat the colour of smoke with china-blue eyes which she was very fond of. The cat was constantly with her, and ran after her wherever she went, and even sat up proudly by her side when she drove out in her fine glass coach.

'Oh, pussy,' said the queen one day, 'you are happier than I am! For you have a dear kitten just like yourself, and I have nobody to play with but you.'

'Don't cry,' answered the cat, laying her paw on her mistress's arm. 'Crying never does any good. I will see what can be done.'

The cat was as good as her word. As soon as she returned from her drive, she trotted off to the forest to consult a fairy who dwelt there, and very soon after, the queen had a little girl who seemed made out of snow and sunbeams. The queen was delighted, and soon the baby began to take notice of the kitten as she jumped about the room and would not go to sleep at all unless the kitten lay curled up beside her.

Two or three months went by, and though the baby was still a baby, the kitten was fast becoming a cat, and one evening when, as usual, the nurse came to look for her to put her in the baby's cot, she was nowhere to be found. What a hunt there was for that kitten, to be sure! The servants, each anxious to find her, as the queen was certain to reward the lucky man, searched in the most impossible places. Boxes were opened that would hardly have held the kitten's paw; books were taken from bookshelves, lest the kitten should have got behind them; drawers were pulled out, for perhaps the kitten might have got shut in. But it was all no use. The kitten had plainly run away, and nobody could tell if it would ever choose to come back.

Years passed away, and one day, when the princess was playing ball in the garden, she happened to throw her ball farther than usual, and it fell into a clump of rose-bushes. The princess of course ran after it at once, and she was stooping down to feel if it was hidden in the long grass when she heard a voice calling her: 'Ingibjorg! Ingibjorg!' it said. 'Have you forgotten me? I am Kisa, your sister!'

'But I never HAD a sister,' answered Ingibjorg, very much puzzled for she knew nothing of what had taken place so long ago.

'Don't you remember how I always slept in your cot beside you, and how you cried till I came? But girls have no memories at all! Why, I could find my way straight up to that cot this moment if I was once inside the palace.'

'Why did you go away then?' asked the princess. But before Kisa could answer, Ingibjorg's attendants arrived breathless on the scene and were so horrified at the sight of a strange cat that Kisa plunged into the bushes and went back to the forest.

The princess was very much vexed with her ladies-in-waiting for frightening away her old playfellow and told the queen, who came to her room every evening to bid her good-night.

'Yes, it is quite true what Kisa said,' answered the queen. 'I should have liked to see her again. Perhaps, some day, she will return, and then you must bring her to me.'

Next morning it was very hot, and the princess declared that she must go and play in the forest, where it was always cool, under the big shady trees. As usual, her attendants let her do anything she pleased and, sitting down on a mossy bank where a little stream tinkled by, they soon fell sound asleep.

The princess saw with delight that they would pay no heed to her, and wandered on and on, expecting every moment to see some fairies dancing round a ring, or some little brown elves peeping at her from behind a tree. But — alas! — she met none of these; instead, a horrible giant came out of his cave and ordered her to follow him. The princess felt much afraid, as he was so big and ugly, and began to be sorry that she had not stayed within reach of help, but as there was no use in disobeying the giant, she walked meekly behind.

They went a long way, and Ingibjorg grew very tired and at length began to cry.

'I don't like girls who make horrid noises,' said the giant, turning round. 'But if you WANT to cry, I will give you something to cry for.' And drawing an axe from his belt, he cut off both her feet, which he picked up and put in his pocket. Then he went away.

Poor Ingibjorg lay on the grass in terrible pain and wondering if she should stay there till she died, as no one would know where to look for her. How long it was since she had set out in the morning she could not tell — it seemed years to her, of course, but the sun was still high in the heavens when she heard the sound of wheels, and then, with a great effort, for her throat was parched with fright and pain, she gave a shout.

'I am coming!' was the answer, and in another moment a cart made its way through the trees, driven by Kisa, who used her tail as a whip to urge the horse to go faster. Directly Kisa saw Ingibjorg lying there, she jumped quickly down and, lifting the girl carefully in her two front paws, laid her upon some soft hay and drove back to her own little hut.

In the corner of the room was a pile of cushions, and these Kisa arranged as a bed. Ingibjorg, who by this time was nearly fainting from all she had gone through, drank greedily some milk, and then sank back on the cushions while Kisa fetched some dried herbs from a cupboard, soaked them in warm water, and tied them on the bleeding legs. The pain vanished at once, and Ingibjorg looked up and smiled at Kisa.

'You will go to sleep now,' said the cat, 'and you will not mind if I leave you for a little while. I will lock the door, and no one can hurt you.' But before she had finished the princess was asleep.

Then Kisa got into the cart, which was standing at the door, and, catching up the reins, drove straight to the giant's cave.

Leaving her cart behind some trees, Kisa crept gently up to the open door, and, crouching down, listened to what the giant was telling his wife, who was at supper with him.

(1100 words)

_-_Le_Chat_botte%CC%81_-_1.png)

_6.jpg)