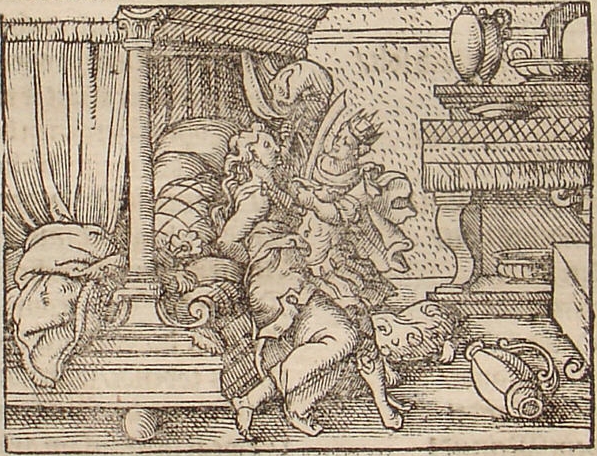

Tereus forces Philomela

Now little was left of Phoebus’s daily labour, and his horses were treading the spaces of the western sky. A royal feast was served at Pandion’s table, with wine in golden goblets. Then their bodies sated, they gave themselves to quiet sleep. But though the Thracian king retired to bed, he was disturbed by thoughts of her, and remembering her features, her gestures, her hands, he imagined the rest that he had not yet seen, as he would wish, and fuelled his own fires, in sleepless restlessness.

Day broke, and Pandion, clasping his son-in-law’s right hand in parting, with tears welling in his eyes, entrusted his daughter to him. ‘Dear son, since affectionate reasons compel it, and both of them desire it (you too have desired it, Tereus), I give her over to you, and by your honour, by the entreaty of a heart joined to yours, and by the gods above, I beg you, protect her with a father’s love, and send back to me, as soon as is possible (it will be all too long a wait for me), this sweet comfort of my old age. You too, as soon as is possible (it is enough that your sister is so far away), if you are at all dutiful, Philomela, return to me!’

So he commanded his daughter and kissed her, and soft tears mingled with his commands. As a token of their promise he took their two right hands and linked them together, and asked them, with a prayer, to remember to greet his absent daughter, and grandson, for him. His mouth sobbing, he could barely say a last farewell, and he feared the forebodings in his mind.

As soon as Philomela was on board the brightly painted ship, and the sea was churned by the oars, and the land left behind them, the barbarian king cried ‘I have won! I carry with me what I wished for!’ He exults, and his passion can scarcely wait for its satisfaction. He never turns his eyes away from her, no differently than when Jupiter’s eagle deposits a hare, caught by the curved talons, in its high eyrie: there is no escape for the captive, and the raptor gazes at its prize.

Now they had completed their journey, and disembarked from the wave-worn ship, on the shores of his country. The king took her to a high-walled building, hidden in an ancient forest, and there he locked her away, she, pale and trembling, fearing everything, in tears now, begging to know where her sister was.

Then, confessing his evil intent, he overcame her by force, she a virgin and alone, as she called out, again and again, in vain, to her father, her sister, and most of all to the great gods. She quivered like a frightened lamb that fails to realise it is free, wounded and discarded by a grey wolf, or like a dove trembling, its feathers stained with its blood, still fearing the rapacious claws that gripped it.

After a brief while, when she had come to her senses, she dragged at her dishevelled hair, and like a mourner, clawed at her arms, beating them against her breasts. Hands outstretched, she shouted ‘Oh, you savage. Oh, what an evil, cruel, thing you have done. Did you care nothing for my father’s trust, sealed with holy tears, my sister’s affection, my own virginity, your marriage vows? You have confounded everything. I have been forced to become my sister’s rival. You are joined to both. Now Procne will be my enemy! Why not rob me of life as well, you traitor, so that no crime escapes you? If only you had done it before that impious act. Then my shade would have been free of guilt. Yet, if the gods above witness such things, if the powers of heaven mean anything, if all is not lost, as I am, then one day you will pay me for this! I, without shame, will tell what you have done. If I get the chance it will be in front of everyone. If I am kept imprisoned in these woods, I will fill the woods with it, and move the stones, that know of my guilt, to pity. The skies will hear of it, and any god that may be there!’

Philomela is mutilated

The king’s anger was stirred by these words, and his fear also. Goaded by both, he freed the sword from its sheath by his side, and seizing her hair gathered it together, to use as a tie, to tether her arms behind her back. Philomela, seeing the sword, and hoping only for death, offered up her throat. But he severed her tongue with his savage blade, holding it with pincers, as she struggled to speak in her indignation, calling out her father’s name repeatedly. Her tongue’s root was left quivering, while the rest of it lay on the dark soil, vibrating and trembling, and, as though it were the tail of a mutilated snake moving, it writhed, as if, in dying, it was searching for some sign of her. They say (though I scarcely dare credit it) that even after this crime, he still assailed her wounded body, repeatedly, in his lust.

He controlled himself sufficiently to return to Procne, who, seeing him returned, asked where her sister was. He, with false mourning, told of a fictitious funeral, and tears gave it credence. Procne tore her glistening clothes, with their gold hems, from her shoulders, and put on black robes, and built an empty tomb, and mistakenly brought offerings, and lamented the fate of a sister, not yet due to be lamented in that way.

Next: Procne's Revenge

(1000 words)